Competency and the Link to Engagement and Performance: If you’re not focused on competency… what ARE you focused on?

At WFSI, we’re laser-focused on competency as THE key to organizational performance. And while there are companies who say they have a competency focus, when you scratch a bit below the surface, you find that things aren’t necessarily what they may appear to be.

One example we’ve seen repeatedly is in recruiting for “entry-level” positions.

A few years ago we did some research where we looked at job postings on a variety of online job sites, specifically for “entry level” roles for individuals with some level of post-secondary education.

Unsurprisingly, most of the jobs we found tended to be technical or administrative – that is “white collar” type roles. We extracted from these postings the types and levels of competency that organizations were looking for.

As “competency geeks”, we look at proficiency using something called a “Dreyfus Scale” (you may not know it by that name, but I guarantee you know it) which is a 5-level scale that ranks proficiency from “novice” at one end to “expert” at the other end (insert reference).

Dreyfus and Dreyfus “Novice to Expert Scale”[1]

| Knowledge | Standard of Work | Autonomy | Coping with Complexity | Perception of Context | |

| Expert | Authoritative understanding of discipline and deep tacit understanding across area of practice | Excellence achieved with relative ease | Able to take responsibility for going beyond existing standards and creating own interpretations | Holistic grasp of complex situations, moves between intuitive and analytical approaches with ease | Sees overall ‘picture’ and alternative approaches; vision of what may be possible |

| Proficient | Depth of understanding of discipline and area of practice | Fully acceptable standard achieved routinely | Able to take full responsibility for own work (and that of others where applicable) | Deals with complex situations holistically. Decision-making is more confident | Sees overall ‘picture’ and how individual actions fit within it |

| Competent | Good working and background knowledge of area of practice | Fit for purpose, but may lack refinement | Able to achieve most tasks using own judgement | Copes with complex situations through deliberate analysis and planning | Sees actions at least partly in terms of longer-term goals |

| Beginner | Working knowledge of key aspects of practice | Straightforward tasks likely to be completed to an acceptable standard | Able to achieve some steps using own judgement, but supervision needed for overall task | Appreciates complex situations but only able to achieve partial resolution | Sees actions as a series of steps |

| Novice | Minimal or ‘textbook’ knowledge without connection to practice | Unlikely to be satisfactory unless closely supervised | Needs close supervision or instruction | Little or no conception of dealing with complexity | Tends to see actions in isolation |

Turns out that a lot of companies are recruiting entry-level employees that they expect to be at the “Proficient”(or even higher) level.

And why wouldn’t you? You want the “best people”, after all (although you can argue whether or not this sort of “grade inflation” helps or hurts companies looking for talent).

But, because we’re competency geeks, we went a little further – we actually went to some of the organizations posting jobs and looked at the management practices and policies for these ‘entry-level’ workers. The results were kind of surprising.

It turns out that a lot of the management processes aren’t designed for “competent” or “proficient” people – they are designed for low performers with low proficiency.

What does the motivational science predict will happen when you hire a capable individual and then put them in a box designed to hold someone less capable?

Yep. They tune out.

Published data from the Q12 in 2017 tells us that employees with a high school diploma or less represent the most engaged group of employees, followed by those with some university or college, followed by those who have a postgraduate degree or who have done postgraduate work. Among the levels of education, employees who completed degrees, but no postgraduate work rank LAST in engagement.

Some other data:

- 68% of university graduates believe they are overqualified for their current job

- Only 21% “strongly agree” that their performance is managed in a way that motivates them to do outstanding work

- Only 18% agree that the employees who perform best grow faster in their current organization.

Having to (and being allowed to) stretch seems to be the key to engagement in younger, well educated workers.

And this brings to mind a quote from Peter Drucker, who wrote: “…the young knowledge worker whose job is too small to challenge and test his abilities either leaves or declines rapidly into premature middle age, soured, cynical, unproductive…” [2]

All of this is predicted by the science. And backed up by empirical data.

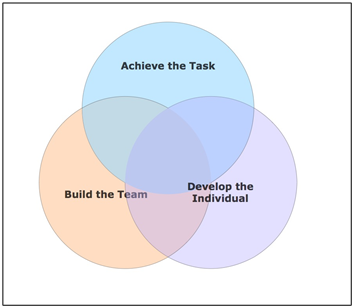

We know that people progress faster and perform better when they are stretching a bit outside their comfort zone – what in education is called the “Zone of Proximal Development”, but which is equally applicable to worker development. By creating the circumstances for people to do work that matters (purpose), that the enjoy (passion) and that they have some control over (autonomy)… but that’s just a bit beyond their present capacity… you create the conditions that lead to mastery and that magic elixir of performance – FLOW.

Organizations that are intentional about this significantly outperform organizations that put people in boxes designed not to promote excellence but to guard against weakness.

What does this all mean?

- Before you hire your next entry-level worker, run your competency requirements for an entry-level worker through a “sanity check” to ensure that it’s realistic. Don’t try to hire years of experience for an entry-level salary.

- Create realistic assessments that will help you rapidly gauge what someone’s competency level really is. (This isn’t as hard as you think – or as a lot of testing companies will want you to believe. See our article on simple competency testing during recruiting).

- Take a hard look at your onboarding and day-to-day management practices, particularly for new workers, and make sure they are structured to support STRENGTH and not to cover up WEAKNESS. This means tailoring your approach to every individual. ONE SIZE FITS NOBODY! If you think that makes a manager’s job more complex and difficult, you’re right. But that’s part of the reason why they get paid more!

- Make a concerted effort to place your team in the “Zone of Proximal Development”, every day.

And watch the benefits: better performance; more engagement; more innovation; more agility and resilience.

And who doesn’t want that?

[2] Drucker, Peter F. The Effective Executive. New York, Harper Collins, 2006 p 83